As part of the Right Here Right Now global summit, held in Oxford and around the world on 4-6 June 2025, it was a pleasure to organise a fascinating and insightful panel discussion on deliberative democracy and its links to climate justice and human rights.

Chaired by Dr Alison Chisholm, the speakers were

- Prof Alan Renwick, Deputy Director of the Constitution Unit, UCL

- Lucy Farrow, Partner, Thinks Insight & Strategy

- Reema Patel, Founder of Elgon Social Research

- Prof Tim Schwanen, Director of the Transport Studies Unit, University of Oxford

- Kris Masih, citizens’ assembly member

- Ben Schachter (concluding comments), UN Human Rights Office

A recording of the event is available below.

We’d highly recommend watching the whole video, but for those would like a taster of the content, we’ve summarised some of the key points in this blog (along with an indication of when each speaker starts).

Citizen engagement to support climate justice

The injustices of climate change are glaring: those hit first and hardest by climate impacts are generally the least responsible for creating emissions, have benefitted least from the burning of fossil fuels, and are least resourced materially to manage the impacts. Ways to mitigate and adapt to climate change mean big changes to many areas of our lives, so to secure public support for solutions to that are effective, acceptable and equitable, citizen engagement is critical. The panel discussed the potential for deliberative democracy to advance such engagement, and thus social, political and policy shifts towards climate justice. Threaded through the discussion were a call to generate a more widespread deliberative culture, and to explore ways to better integrate deliberative processes with an often non-deliberative political milieu.

What is deliberative democracy? (5:52)

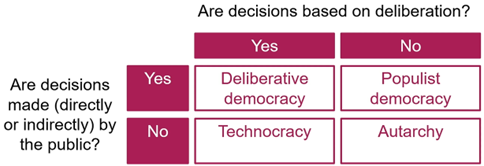

Alan Renwick, Professor of Democratic Politics and Deputy Director of the Constitution Unit at UCL began by setting out the meaning of deliberative democracy: decision-making by and for all the people, through a careful process of weighing evidence and considering trade-offs, undertaken in a spirit of open-minded listening. He contrasted it with the alternatives: decision-making that is deliberative but not democratic (technocracy), democratic but not deliberative (populist democracy, or democracy as we mostly experience it), or decision-making that is neither deliberative nor democratic (autarchy).

In contrast with populist democracy, deliberative democratic processes allow longer time horizons and can overcome powerful vested interests, making space for more marginalised voices and perspectives. Compared to technocracy, deliberative democracy can better consider the complex and wide-ranging perspectives, circumstances and values of a diverse population and therefore generate solutions that are more likely to be perceived as fair.

Alan alerted us to possible pitfalls: running deliberative processes well is difficult and requires energy, expertise and resources. As these processes interact with the wider political and social environment, recommendations must be taken seriously by elected representatives and prevented from becoming a political football.

He concluded that deliberative democracy holds substantial promise, but this requires a shift beyond holding a series of isolated events towards a broader deliberative and participatory political culture.

Visible deliberation for implementation and community resilience (19:15)

Lucy Farrow is a deliberative engagement specialist with research agency Thinks, and a visiting Fellow at Lancaster University’s Climate Citizens initiative.

Picking up Alan’s call for a more deliberative culture, she began with the unexpected provocation that we should “stop doing climate assemblies.” She argued that the Climate Citizens recent review of the outputs of 30 UK climate deliberative mini-publics, shows they have largely established a mandate for government at national and local levels to take climate action. She suggested that the focus should now move from generating broad aspirations and recommendations to deliberation on more technocratic elements of policy implementation, following the example of the Climate Change Committee’s Citizens’ Panel on Net Zero.

Lucy went on to suggest that, where deliberative processes aim to ensure and demonstrate legitimate decision-making with the public, this must be signalled more strongly and visibly, as was demonstrated by the high-profile Change NHS public engagement exercise on the future of the NHS.

She concluded with the remark that deliberative democratic processes can, and should, be designed to contribute to stronger democracy and climate justice, building community resilience and agency in the maxi-public. This can be achieved by giving assembly members tools to run further deliberative events with wider reach, as exemplified by the People’s Climate Jury carried out in Preston by Shared Future.

Global deliberation for local solidarity and international civic infrastructure (33.50)

Reema Patel, a practitioner and thought leader in the field of deliberative democracy, is establishing the Global Citizens’ Assembly (GCA) in 2025 together with the ISWE Foundation, and directed the Global Science Partnership for COP26. Reema’s blog explores the significant challenges for organisers of selecting 100 assembly members by sortition to reflect a snapshot of the global human family, worldwide – but the Global Citizens Assembly does not shirk a challenge, and its ambitions stretch beyond running the assembly itself.

Continuing the theme of spreading deliberative democracy more widely, the GCA aims to build a “world of resilient local communities that have the tools and confidence to make fair, effective decisions, through inclusive community assemblies that facilitate learning, build solidarity and have clear pathways to local and global action” using the assemblis platform.

The GCA also incorporates a campaign to communicate and influence widespread changes in practice and ethos through culture, movement and influencers. To address the paucity of opportunities in global governance for citizens to shape climate action, it aims to develop a coalition of civic infrastructure at local, national and international levels, backed by the Brazilian government.

Deliberation for cognitive justice (46:35)

Tim Schwanen, Professor of Transport Geography and Director of the Transport Studies Unit at the University of Oxford, has given evidence at many citizens’ assemblies. He highlighted their capacity to promote cognitive justice by allowing different knowledge systems to be treated equally, and to prize open and examine the technocratic forms of knowledge that tend to dominate the transport narrative.

For example, in considering the introduction of particular interventions, assembly members might wish to learn from the experiences of other successful cities – yet political systems, cultures and governance structures are very different in different contexts. A citizens’ assembly provides the space to elaborate more nuanced positions and to explore critically how the effects of interventions are mediated by cultures and habits.

Tim echoed Alan’s warnings about the challenges to the transformative potential of climate assemblies that are inherent in the wider context of technocracy, political opportunism and populism. While, in isolation, they are not enough to make the transition socially just, he concluded that our understanding of how to design, deliver and follow-up citizens’ assemblies is constantly improving, and called for on-going experimentation as a significant element of improving our cities.

Deliberation for grace and the greater good (58:10)

Kris Masih compellingly brought an assembly member perspective, highlighting the need for engagement exercises to bear fruit if they are to bolster trust in government. Recognising their advisory, non-binding, role, she underlined the importance that recommendations – which, in the case of the assembly she was part of, were realistic and reasonable – receive a considered response from the commissioning body (often a local authority) and are incorporated in the broader mix of decision-making.

She described how she and her fellow assembly members, through understanding different perspectives, became less focused on their own individual whims. She reflected that, if all someone can see is their own perspective, that’s all they can draw on. Kris had seen, first hand, how informed conversations during the assembly process encouraged people from different backgrounds and experiences to engage in constructive ways and to work hard to collaborate for the greater good, rather than “winning” for “their own side”.

The impact, she said, went beyond the event itself. Being aware of the wider issues, and understanding the policy process and views of different stakeholders, she came away from the citizens’ assembly enthusiastic to talk about transport and health wherever she went. In her closing comments, Kris captured the views of many who take part in deliberative processes, in relation to social cohesion:

“When the public understands wider views, they will bring more grace for decisions that don’t benefit them personally, because they understand the benefit more widely. Instead of seeing the establishment as the enemy or the problem, they feel part of the solution and you’ll get greater buy-in and more commitment to policy change if people understand why it’s happening and how it will affect the world widely.”

Questions from the floor: Integration, institutionalisation and sortition to replace representation? (1:08:00)

The presentations stimulated a lively Q&A session, covering a range of critical questions which are summarised briefly here, but can be seen in full on the recording:

Q: How can deliberative processes be integrated or institutionalised into our political system?

A: It depends on the purpose and questions being asked, and where and by whom decisions are taken, but we can look to Denmark and Ostbelgien (Eastern Belgium) for examples.

Q: Could sortition replace elected representation?

A: This raises concerns about accountability – reforming the culture of existing political institutions and structures is preferable.

Q: Is it ever better to present only technical evidence in a deliberative process to avoid emotionally-loaded controversy and bias?

A: Deliberative processes that invite a wide range of perspectives and types of evidence can effectively help move from divided public opinion to less polarised, more considered judgement.

Deliberative democracy and human rights

Ben Schachter coordinates the Climate Change and Environment Unit in the UN Human Rights office in Geneva. He drew the session to a close by highlighting alignment between the pursuit of more deliberative democracy and the IPCC’s finding that participatory and inclusive, human rights-based approaches, grounded in equity, lead to more effective policy outcomes. The Brazilian hosts of COP30 are committed to facilitating participatory dialogue, recognising that the enactment of the human right to free and active participation enables better policy-making and climate justice.

Thanks to everyone who took part

We would like to thank all the speakers for their astute and thought-provoking contributions to this exploration of the role of deliberative democracy in the service of climate justice. We ourselves echo their call for a more widespread deliberative culture, and if you agree, we encourage you to contact your political representatives to let them know. We firmly believe that a deliberative approach to democracy would better serve the places they represent, their communities and the systems that support them, in a more equitable way.

Alison Chisholm is a Research Associate at the GCHU and a researcher in the Nuffield Department of Primary Care Health Sciences.