MMath Mathematics and Statistics student Callum Young walks through some of the findings of his spring internship with the GCHU, exploring the complex challenges of development in Oxford and whether making better use of empty homes can alleviate tensions in housing.

The Situation in Oxford:

For the first part of the internship, I had the opportunity to join interviews of local experts which were conducted to get an understanding of the local planning landscape and to get their ideas on how provisioning systems in the city can be transformed to align sustainable development with social equity considerations. They shared their expertise, drawing on their careers working on these issues. One theme that stuck out across the interviews was how unique the struggles are that Oxford faces. One of the experts sets the scene well:

“Oxford is extremely unusual as a city in England. It’s the largest city between London and Birmingham, but it’s only 160,000 people. It would normally be much bigger. There was a plan in 1927 for a city, twice the size, and then, in effect, the colleges and universities stopped that happening, bought up the land on the edge. So it’s a weirdly constrained, unusual city”

They go on to explain…

“It’s a bizarre situation. Head teachers of the local schools tend to be able to buy but often they’re 30 minutes out. School teachers are living like students in shared houses, and they managed to last about three or four years. They can’t have children. In effect, they are servants.”

Interview with local expert in social geography, 9/4/25

This highlights the complex relationship between the Universities and the town. When most people think of Oxford they probably think of the University, but not many people appreciate how its interaction with the city indirectly causes unique challenges for things including local primary and secondary education, where the unaffordability and lack of housing cause a high turnover of teachers. The pressures aren’t just limited to schools. The housing crisis has knock-on effects on other key services. NHS staff and care workers also struggle to live locally, pushing critical services to the brink as commuting times rise and retention drops. The dominance of the University has created a distorted local economy, one that generates global prestige and investment, but leaves everyday infrastructure, including schools, housing, and transport under strain.

Vacant Dwellings as Potential Levers:

Despite the dire need for housing in Oxford, there are over 1500 homes not in use in the city. For the second part of the internship, I analysed data on empty homes across the country, to try to understand the underlying reasons that homes might be left empty, to compare the situation in Oxfordshire to the rest of England, and to understand whether the revival of empty homes can help alleviate tensions in housing.

I started by collating data from different sources for each district of England, including factors such as house prices5, health and proximity factors3, and indices of deprivation4. I then developed a linear regression model to test their relationship with the proportion of empty homes, to see if there might be key reasons why these homes are left empty. Various of the analysed factors had a statistically significant effect, and together accounted for 30 per cent of the variance in the empty homes data.

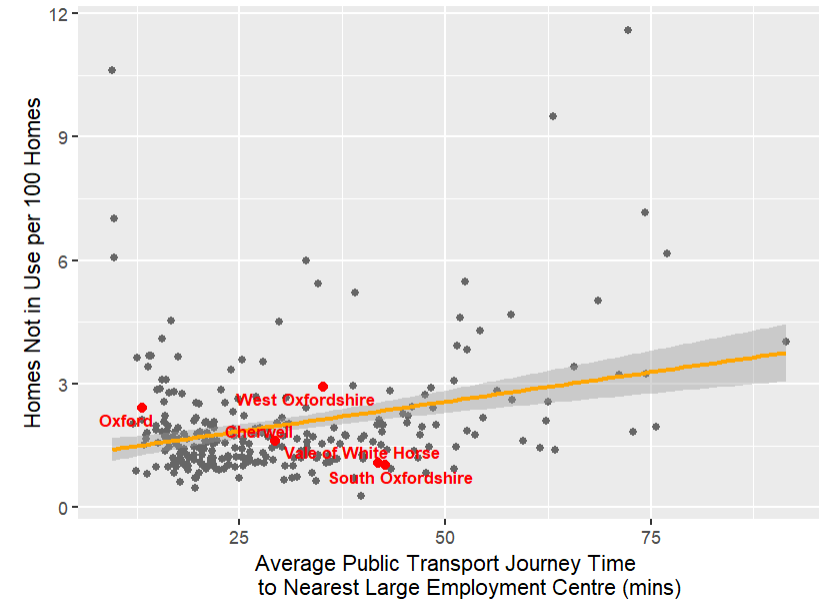

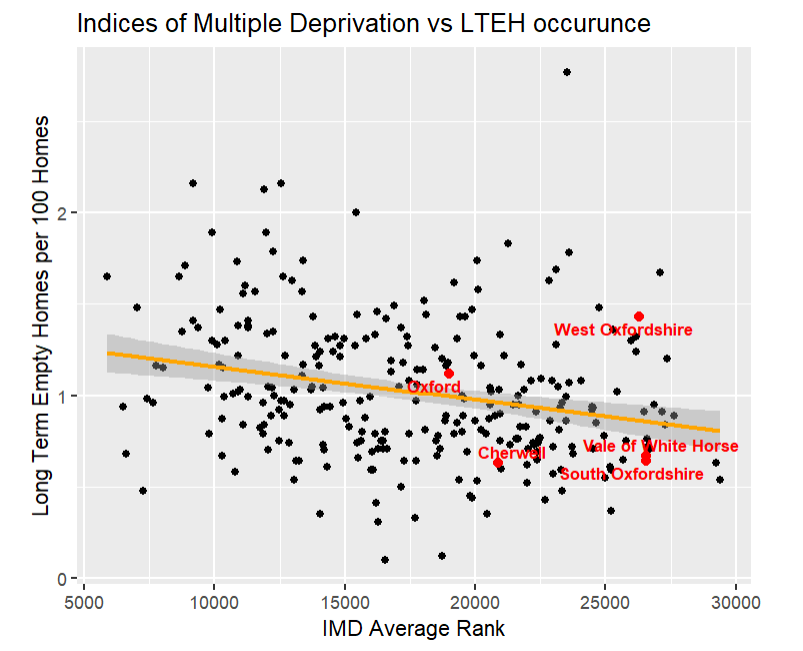

For example, the analysis suggests that areas with longer average journey times to employment centres tend to have a higher proportion of long term empty homes. This could indicate that poor accessibility to job opportunities makes certain districts less attractive to live in, particularly for working age residents, leading to higher vacancy rates over time. In such places, limited economic activity and weaker transport infrastructure may discourage new occupants to settle. However, it’s important to note that the relationship is relatively weak, meaning that journey time alone doesn’t explain most of the variation and other factors like local housing demand, deprivation, and demographic trends are likely playing a significant role. Additionally, the direction of influence isn’t guaranteed, it’s possible that areas with high numbers of empty homes also see reduced demand for employment services, reinforcing the isolation. Overall, while accessibility appears to be part of the story, it’s just one piece in a much broader and more complex picture of housing use across England. The following graph uses a broader metric of the deprivation of an area, the IMD and investigates its effect on the number of long term empty homes:

The most deprived areas were predicted by the model to have 57% more long term empty homes (LTEHs) than the least deprived areas. West Oxfordshire has a large proportion of empty homes despite being very close to the bottom of the deprivation ranking. They have introduced a “Long term empty property strategy”6 plan which walks through their ideas of how they will reduce this number, through means such as enforced sales and empty property management orders.

It is certainly a very complex issue with many factors that come into play, but another promising path to getting more empty homes on the market is by introducing large council tax premiums on them. This has already been implemented by many councils including Oxford City Council who have introduced the maximum rates allowed by central government which go up to 300% extra council tax for properties left empty 10 years and over.

Conclusion

I really enjoyed my two weeks with the GCHU this April. The experience gave me valuable insights into the planning sector and helped me better understand the complex challenges Oxford faces. It also allowed me to apply data analysis to real-world issues, deepening my practical skills and appreciation for how data can inform decision making.

References:

1: Number of vacant and second homes, England and Wales – Office for National Statistics, Figure 4, url: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/housing/bulletins/numberofvacantandsecondhomesenglandandwales/census2021

Last accessed: 17th April 2025

2: England long-term empty and second homes to show total % of housing not in residential use on a long-term basis, by local authority area, by Action on Empty Homes url: https://www.actiononemptyhomes.org/facts-and-figures

Last accessed: 17th April 2025

3: Transport accessibility to local services: a journey time tool – Raw Data files – National Audit Office (NAO) url: https://www.nao.org.uk/transport-accessibility-to-local-services-a-journey-time-tool-raw-data-files/

Last accessed: 17th April 2025

4: English Indices of Deprivation 2019 url: www.gov.uk/government/statistics/english-indices-of-deprivation-2019

Last accessed: 17th April 2025

5: UK House Price Index: monthly price statistics-26th March 2025 data – Office for National Statistics url: https://www.ons.gov.uk/economy/inflationandpriceindices/datasets/ukhousepriceindexmonthlypricestatistics

Last accessed: 17th April 2025

6: Long Term Empty Property Strategy 2024 to 2029 – West Oxfordshire, url: https://www.westoxon.gov.uk/housing/empty-homes/

Last accessed: 17th April 2025